Northern Ireland: Parties of sectarian conflict warn of renewed clashes

Unionists and loyalists think 23-year-old peace might come to an end if riots escalate

By Ahmet Gurhan Kartal

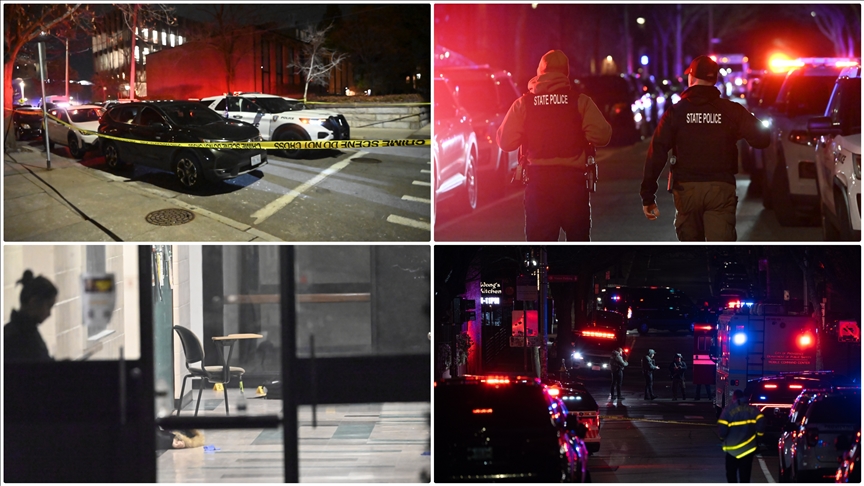

LONDON (AA) – An almost-forgotten conflict in UK-ruled Northern Ireland made headlines in April when pop-up protests and riots caused the injury of more than 100 police officers.

The rioters used petrol bombs to burn down a public bus, cars, and commercial garbage bins and pelted police vans with bricks and other missiles, in a painful reminder of the years the British call “the Troubles.”

The street incidents were carried out by people known locally as loyalists. They are unionists largely of the Protestant persuasion who defend the ideal of a United Kingdom, now angered due to the Northern Ireland protocol of the Brexit agreement the central UK government in Westminster inked last year with the EU.

The protocol, the loyalists think, created a de facto border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, imposing a border check on goods between Great Britain and the region.

“The main reason at the moment is what's been called the Northern Irish protocol and what we call the border in the Irish Sea,” a former British soldier said, confirming the loyalists’ anger.

“And if I can just point behind me, that is now the border between Northern Ireland and Great Britain,” Richard Inman, 52, said, speaking at the Groomsport Harbour in Belfast, Northern Ireland’s capital.

“So really what's happened is Northern Ireland has now been separated from the rest of the United Kingdom by this de facto border. And to all intents and purposes, we've been shunted into an economic united Ireland,” Inman told Anadolu Agency.

Accusing the EU of demanding a border in the post-Brexit era, Inman added: “Sadly, the British government has signed up to it and the Irish government for their own reasons – which goodness knows why they did it – really bullied the British government into agreeing to the protocol and basically allowing the EU to annex Northern Ireland.”

“So you've got a situation where Northern Ireland is really within the sphere of the European Union and the rest of the United Kingdom has left the European Union,” he said, calling the situation “totally unacceptable.”

- Things could get worse

“Will the street protests lead to something akin to the Troubles?” Inman asked, referring to the decades of conflict in Northern Ireland from the 1960s to the late ‘90s

“Hopefully not. But the reality is in Northern Ireland, you don't know.”

Citing a 1998 petrol bombing incident in Ballymoney, a largely Protestant village north of Belfast, which claimed the lives of three Catholic boys, Inman warned that things in Northern Ireland can rapidly escalate.

“Things can very, very quickly spiral out of control,” he said.

The events of two weeks ago “could very, very easily have gone very, very badly wrong. And thankfully, they didn't,” he added.

“But you can never say never in this country. And that's what we've got to be very, very aware of.”

- Possible backlash

Also speaking to Anadolu Agency, Sean Murray, a prominent figure of the Sinn Fein party and former member of the IRA Army Council, warned about a possible backlash from Irish nationalists.

“We had a particularly vicious spell of violence this past week here in relation to the process started by unionist loyalists, but they say it’s in relation to the protocol,” he said.

Murray said opposing the Northern Ireland protocol is “an issue around identity,” as the loyalists think “their British identity has been diluted because this protocol … represents a border down the Irish Sea.”

“The problem is that they bring protests on to the interface [gate] like this. There's going to be a reaction to it,” Murray added, mentioning how loyalist protesters threw petrol bombs to the Catholic side of the Peace Wall in Belfast.

“And we've seen that last week because [Irish nationalist] people thought that the area was being invaded.”

Murray added that the local history has to be understood.

He said decades ago loyalists burned down streets in the city, and the latest incidents were a "strong signal" to those who live here.

“I am worried because once you have tensions like that, and there's a provocation … then you have the law of unintended consequences coming into play.”

“Like last week, this gate here which represents part of the peace line was breached, and they were actually coming through it with petrol bombs and throwing petrol bombs,” he said.

Murray added: “Petrol bombs were flying here. The bricks were flying here. It's only too sheer luck that nobody was killed or seriously injured. And this can continue on all summer and night.”

Evoking the violent history of marches in hostile territory, he added: “When they [loyalists] protest in the middle of the unionist areas, the problem is I think it's a protest here that's going to end up in conflict and they know that.”

The conflict “may get them more media attention. It's a vicious circle,” he warned.

Asked if the country would once again be engulfed in an armed conflict between Catholics and Protestants, Murray responded cautiously, saying: “No, hopefully not.”

If the riots continued, he warned, "you don't know what's going to happen."

- Fragile peace

The border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic was one of the thorniest issues in Brexit negotiations between the UK and EU.

The Brexit deal aligns Northern Ireland with the EU, avoiding a hard border for the time being.

Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU in a 2016 referendum, but it is feared the Brexit process could trigger enmity in the region.

The Troubles – an era of conflict between the British government and pro-British paramilitaries on one side and Irish Republicans and nationalists on the other – ended in 1998 when the Belfast Agreement put an end to decades of armed struggle in the divided UK region of Northern Ireland.

The UK and the Republic of Ireland signed the deal, brokered by the US and eight political parties in Northern Ireland, on April 10, 1998.

The deal, dubbed the Good Friday Agreement, largely saw the end of the Troubles-era violence, in which 3,500 people lost their lives.

However, splinter IRA groups are still active in the area.

Kaynak:![]()

This news has been read 259 times in total

Türkçe karakter kullanılmayan ve büyük harflerle yazılmış yorumlar onaylanmamaktadır.